It’s Not about Cell Phones

November 7, 2017

Eric Hill, Department of Psychological Science

For years, I tried to find a way to reduce classroom cell phone use without increasing resentment. Like nearly all my best ideas, I stole this one from someone else. Here, most of the credit goes to Dr. Louise Katz, Professor of Psychology at Columbia State Community College, for an article she wrote in the Chronicle. You can find a copy here.1 One thing I’ve learned after nearly a decade of stealing ideas from other teachers is that you have to tweak them to fit your own style.

How it works (or, at least, this is what I do)

- Buy a calculator holder. Here’s the one I use.

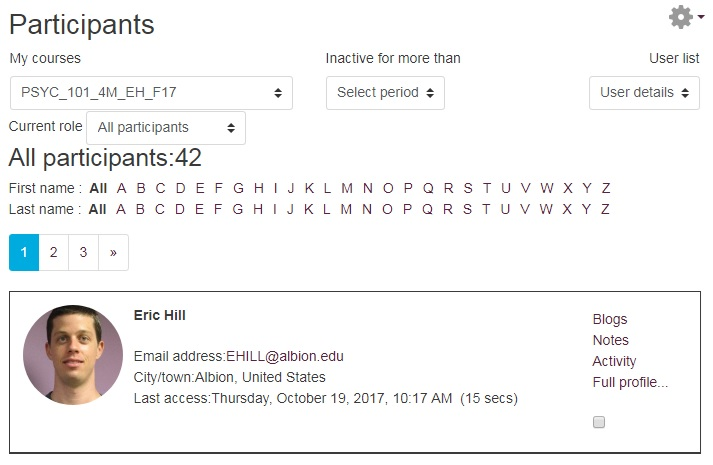

- On the Course Web, print the Participants page with the ‘User details’ option. Cut out individual pictures with names, fold between the names and pictures to make flashcards, learn students’ names and then try to guess them all on the first day of class.

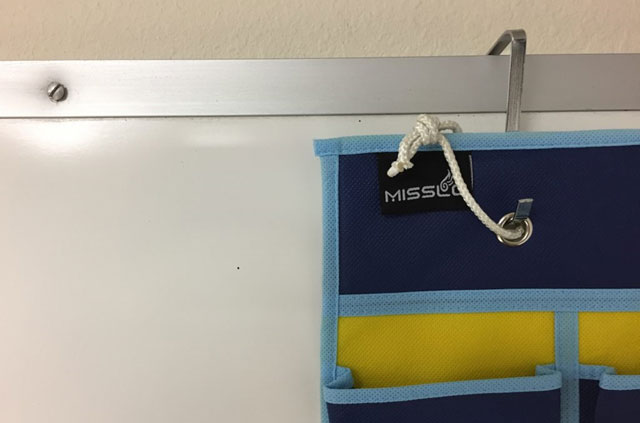

- You’ll need to find a place to hang the holder each day. In rooms with chalkboards, the existing hooks are a bit too big to fit through the grommets. I just made some rope loops as seen here.

In rooms with a whiteboard, you can use the hooks that come with the holder. You’ll need to loosen the whiteboard screws just slightly to slide the hooks into place behind the board.

- On the second day of class, explain the policy. “Every day at the start of class, I will come in and take a picture of this cell phone holder. You can earn up to 10 bonus points in the class as a percentage of the number of times your phone is in the pictures. So, if I take 20 pictures, and your phone is in 15 of them, you get 15/20 = 75% x 10 = 7.5 bonus points. You can think of those points as being added directly to a test. It’s totally optional, and you can change your mind from day to day. If you decide to put your phone in the holder, any time you need to use it, feel free to stand up quietly, grab your phone, go out into the hall, do whatever you need to do, and then just come on back in whenever you’re done. Believe or not, I actually get way more distracted when students try to hide their phones and type on them in class. So please, don’t hesitate to just go out in the hall any time you need to use your phone.” This is all 100% true for me, by the way.

Show some slides with science about how cell phone use is related to lower GPAs. Here 3 are the slides I use.

Have students choose a number on the holder and ‘sign it out.’ I use this grid. 4

- The first time you see a student using their phone in their lap in class, just ask them politely, by name (see Step 2), to head out into the hall if they don’t mind. The student will usually quickly apologize and say that they’ll just put the phone away. That’s when I say something along the lines of, “Oh no, no, really, it’s okay, I don’t mind at all. I know everybody needs to use their phone every once in a while. It’s really no big deal. Just head out there and come back whenever you’re done.” The student will likely insist on putting the phone away, but I find it helpful to reassure them that it’s totally fine. Keep generously acquiescing nearly up to, but not quite to, the point where it becomes awkward. This part is important to gently establish a strong social norm for everyone without having the student in question actually lose face in the exchange.

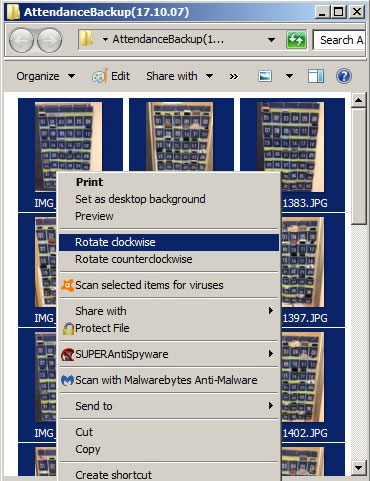

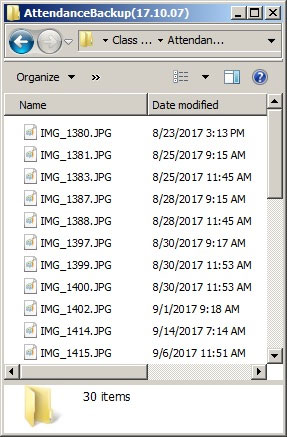

- Tally up the absences. I find that the quickest way to count them up is to download the images to your computer, open the first image with Windows Photo Viewer, and then just use the right arrow key on the keyboard to quickly scroll through. You might need to rotate all the images. Just highlight them all in the folder, right click, and rotate. I focus on one number/pocket with each pass, count the number of times that phone is in the holder, and then move on to the next number.

You can also post the photos and file details on the course web in case student have questions about dates they missed.

Why it works (I think)

The first comment below Katz’s original article is from a person identifying themselves as Steven Michels—”This is a great idea. But it’s also sad. The students can’t seem to control themselves. Clearly, we are dealing with addicts here.”

A cell phone is really a device that allows you to carry all your friends around with you in your pocket and hang out with them anytime you want. Are students addicted to friendship? Sure, but so are most other human beings. I was talking with Dr. Barry Wolf about this phone approach, and he was saying how, for some students (and really a lot of people in general) being asked to put away your cell phone under the threat of losing course points is really a sort of unreasonable request. It’s just so easy when the phone is right there and the motivation for social interaction is so strong. The present method gives students a really easy choice. I’ve so far had one student out of now close to 200 that did not give up their phone on a consistent basis.

And, this method also gives students the choice to access their phones any time. However, students rarely actually get up to use the phone. In my intro psych. class of 40 students, it happens maybe once a week, because, as Barry noted, we’re basically increasing the threshold that must be overcome to use the phone. The payoff is no longer worth the effort and negative attention. The choice to give up the phone is an easy one to make. The choice to get up to use it during class is a surprisingly difficult one to make. But, the fact that these choices exist seems to work to prevent any resentment on the part of the students.